Cue sports are a wide variety of games of skill played with a cue, which is used to strike billiard balls and thereby cause them to move around a cloth-covered table bounded by elastic bumpers known as cushions. Cue sports are also collectively referred to as billiards, though this term has more specific connotations in some varieties of English.

There are three major subdivisions of games within cue sports:

- Carom billiards, played on tables without pockets, typically ten feet in length, including straight rail, balkline, one-cushion carom, three-cushion billiards, artistic billiards, and four-ball

- Pocket billiards (or pool), played on six-pocket tables of seven, eight, nine, or ten-foot length, including among others eight-ball (the world’s most widely played cue sport[1]), nine-ball (the dominant professional game), ten-ball, straight pool (the formerly dominant pro game), one-pocket, and bank pool

- Snooker, English billiards, and Russian pyramid, played on a large, six-pocket table (dimensions just under 12 ft by 6 ft), all of which are classified separately from pool based on distinct development histories, player culture, rules, and terminology.

Billiards has a long history from its inception in the 15th century, with many mentions in the works of Shakespeare, including the line “let’s to billiards” in Antony and Cleopatra (1606–07). Enthusiasts of the sport have included Mozart, Louis XIV of France, Marie Antoinette, Immanuel Kant, Napoleon, Abraham Lincoln, Mark Twain, George Washington, Jules Grévy, Charles Dickens, George Armstrong Custer, Theodore Roosevelt, Lewis Carroll, W. C. Fields, Babe Ruth, Bob Hope, and Jackie Gleason.

History

[edit]

All cue sports are generally regarded to have evolved into indoor games from outdoor stick-and-ball lawn games,[2] specifically those retroactively termed ground billiards,[3] and as such to be related to the historical games jeu de mail and palle-malle, and modern trucco, croquet, and golf, and more distantly to the stickless bocce and bowls.

The word billiard may have evolved from the French word billart or billette, meaning ‘stick’, in reference to the mace, an implement similar to a golf putter, and which was the forerunner to the modern cue; however, the term’s origin could have been from French bille, meaning ‘ball’.[4] The modern term cue sports can be used to encompass the ancestral mace games, and even the modern cueless variants, such as finger billiards, for historical reasons. Cue itself came from queue, the French word for ‘tail‘. This refers to the early practice of using the tail or butt of the mace, instead of its club foot, to strike the ball when it lay against a rail cushion.[4]

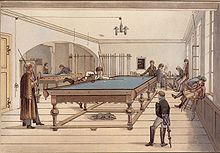

A recognizable form of billiards was played outdoors in the 1340s, and was reminiscent of croquet. King Louis XI of France (1461–1483) had the first known indoor billiard table.[4] Louis XIV further refined and popularized the game, and it swiftly spread among the French nobility.[4] While the game had long been played on the ground, this version appears to have died out (aside from trucco) in the 17th century, in favor of croquet, golf and bowling games, even as table billiards had grown in popularity as an indoor activity.[4]

James VI and I had a “bilzeart burde” covered with green cloth at Holyrood Palace in 1581.[5] The imprisoned Mary, Queen of Scots, had a billiard table at Tutbury Castle.[6] She complained when her table de billiard was taken away (by those who eventually became her executioners, who were to cover her body with the table’s cloth).[4] A 1588 inventory of the Duke of Norfolk‘s estate included a “billyard bord coered with a greene cloth … three billyard sticks and 11 balls of yvery”.[4] Billiards grew to the extent that by 1727, it was being played in almost every Paris café.[4] In England, the game was developing into a very popular activity for members of the gentry.[4]

By 1670, the thin butt end of the mace began to be used not only for shots under the cushion (which itself was originally only there as a preventative method to stop balls from rolling off), but players increasingly preferred it for other shots as well. The footless, straight cue as it is known today was finally developed by about 1800.[4]

Initially, the mace was used to push the balls, rather than strike them. The newly developed striking cue provided a new challenge. Cushions began to be stuffed with substances to allow the balls to rebound, in order to enhance the appeal of the game. After a transitional period where only the better players would use cues, the cue came to be the first choice of equipment.[4]

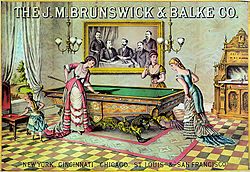

The demand for tables and other equipment was initially met in Europe by John Thurston and other furniture makers of the era. The early balls were made from wood and clay, but the rich preferred to use ivory.[4]

Early billiard games involved various pieces of additional equipment, including the “arch” (related to the croquet hoop), “port” (a different hoop, often rectangular), and “king” (a pin or skittle near the arch) in the early 17th to late 18th century,[7][4] but other game variants, relying on the cushions (and pockets cut into them), were being formed that would go on to play fundamental roles in the development of modern billiards.[4]

The early croquet-like games eventually led to the development of the carom billiards category. These games are played with three or sometimes four balls on a table without holes in which the goal is generally to strike one object ball with a cue ball, then have the cue ball rebound off of one or more of the cushions and strike a second object ball. Variations include straight rail, balkline, one-cushion, three-cushion, five-pins, and four-ball, among others.

One type of obstacle remained a feature of many tables, originally as a hazard and later as a target, in the form of pockets, or holes partly cut into the table bed and partly into the cushions, leading to the rise of pocket billiards, including “pool” games such as eight-ball, nine-ball, straight pool, and one-pocket; Russian pyramid; snooker; English billiards; and others.

In the United States, pool and billiards had died out for a bit, but between 1878 and 1956 the games became very popular. Players in annual championships began to receive their own cigarette cards. This was mainly due to the fact that it was a popular pastime for troops to take their minds off battle. However, by the end of World War II, pool and billiards began to die down once again. It was not until 1961 when the film The Hustler came out that sparked a new interest in the game. Now the game is generally well-known and has many players of all different skill levels.[8]

As a sport

[edit]

The games with regulated international professional competition, if not others, have been referred to as “sports” or “sporting” events, not simply “games”, since 1893 at the latest.[9] Quite a variety of particular games (i.e., sets of rules and equipment) are the subject of present-day competition, including many of those already mentioned, with competition being especially broad in nine-ball, snooker, three-cushion, and eight-ball.

Snooker, though a pocket billiards variant and closely related in its equipment and origin to the game of English billiards, is a professional sport organized at an international level, and its rules bear little resemblance to those of modern pool, pyramid, and other such games.

A “Billiards” category encompassing pool, snooker, and carom has been part of the World Games since 2001.

Equipment

[edit]

Main category: Cue sports equipment

Billiard balls

[edit]

Main article: Billiard ball

Billiard balls vary from game to game, in size, design and quantity.

Russian pyramid and kaisa have a size of 68 mm (2+11⁄16 in). In Russian pyramid there are 16 balls, as in pool, but 15 are white and numbered, and the cue ball is usually red.[10] In kaisa, five balls are used: the yellow object ball (called the kaisa in Finnish), two red object balls, and the two white cue balls (usually differentiated by one cue ball having a dot or other marking on it and each of which serves as an object ball for the opponent).

Carom billiards balls are larger than pool balls, having a diameter of 61.5 mm (2+7⁄16 in), and come as a set of two cue balls (one colored or marked) and an object ball (or two object balls in the case of the game four-ball).

Standard pool balls are 57.15 mm (2+1⁄4 in), are used in many pool games found throughout the world, come in sets of two suits of object balls, seven solids and seven stripes, an 8 ball and a cue ball; the balls are racked differently for different games (some of which do not use the entire ball set). Blackball (English-style eight-ball) sets are similar, but have unmarked groups of red and yellow balls instead of solids and stripes, known as “casino” style. They are used principally in Britain, Ireland, and some Commonwealth countries, though not exclusively, since they are unsuited for playing nine-ball. The diameter varies but is typically slightly smaller than that of standard solids-and-stripes sets.

Snooker balls are smaller than American-style pool balls with a diameter of 52.5 mm (2+1⁄16 in), and come in sets of 22 (15 reds, 6 “colours“, and a cue ball). English billiard balls are the same size as snooker balls and come in sets of three balls (two cue balls and a red object ball). Other games, such as bumper pool, have custom ball sets.

Billiard balls have been made from many different materials since the start of the game, including clay, bakelite, celluloid, crystallite, ivory, plastic, steel and wood. The dominant material from 1627 until the early 20th century was ivory. The search for a substitute for ivory use was not for environmental concerns, but based on economic motivation and fear of danger for elephant hunters. It was in part spurred on by a New York billiard table manufacturer who announced a prize of $10,000 for a substitute material. The first viable substitute was celluloid, invented by John Wesley Hyatt in 1868, but the material was volatile, sometimes exploding during manufacture, and was highly flammable.[11][12]

Tables

[edit]

Main article: Billiard table

There are many sizes and styles of billiard tables. Generally, tables are rectangles twice as long as they are wide. Table sizes are typically referred to by the nominal length of their longer dimension. Full-size snooker tables are 12 feet (3.7 m) long. Carom billiards tables are typically 10 feet (3.0 m). Regulation pool tables are 9-foot (2.7 m), though pubs and other establishments catering to casual play will typically use 7-foot (2.1 m) tables which are often coin-operated, nicknamed bar boxes. Formerly, ten-foot pool tables were common, but such tables are now considered antiques.

High-quality tables have a bed made of thick slate, in three pieces to prevent warping and changes due to temperature and humidity. The slates on modern carom tables are usually heated to stave off moisture and provide a consistent playing surface. Smaller bar tables are most commonly made with a single piece of slate. Pocket billiards tables of all types normally have six pockets, three on each side (four corner pockets, and two side or middle pockets).

Cloth

[edit]

Main article: Baize

All types of tables are covered with billiard cloth (often called “felt”, but actually a woven wool or wool/nylon blend called baize). Cloth has been used to cover billiards tables since the 15th century.

Bar or tavern tables, which get a lot of play, use “slower”, more durable cloth. The cloth used in upscale pool (and snooker) halls and home billiard rooms is “faster” (i.e., provides less friction, allowing the balls to roll farther across the table bed), and competition-quality pool cloth is made from 100% worsted wool. Snooker cloth traditionally has a nap (consistent fiber directionality) and balls behave differently when rolling against versus along with the nap.

The cloth of the billiard table has traditionally been green, reflecting its origin (originally the grass of ancestral lawn games), and has been so colored since at least the 16th century, but it is also produced in other colors such as red and blue.[13] Television broadcasting of pool as well as 3 Cushion billiards prefers a blue colored cloth which was chosen for better visibility and contrast against colored balls.

Rack

[edit]

Main article: Rack (billiards)

A rack is the name given to a frame (usually wood, plastic or aluminium) used to organize billiard balls at the beginning of a game. This is traditionally triangular in shape, but varies with the type of billiards played. There are two main types of racks; the more common triangular shape which is used for eight-ball and straight pool and the diamond-shaped rack used for nine-ball.

There are several other types of less common rack types that are also used, based on a “template” to hold the billiard balls tightly together. Most commonly it is a thin plastic sheet with diamond-shaped cut-outs that hold the balls that is placed on the table with the balls set on top of the rack. The rack is used to set up the “break” and removed once the break has been completed and no balls are obstructing the template.

Cues

[edit]

Main article: Cue stick

Billiards games are mostly played with a stick known as a cue. A cue is usually either a one-piece tapered stick or a two-piece stick divided in the middle by a joint of metal or phenolic resin. High-quality cues are generally two pieces and are made of a hardwood, generally maple for billiards and ash for snooker.

The butt end of the cue is of larger circumference and is intended to be gripped by a player’s hand. The shaft of the cue is of smaller circumference, usually tapering to an 0.4 to 0.55 inches (10 to 14 mm) terminus called a ferrule (usually made of fiberglass or brass in better cues), where a rounded leather tip is affixed, flush with the ferrule, to make final contact with balls. The tip, in conjunction with chalk, can be used to impart spin to the cue ball when it is not hit in its center.

Cheap cues are generally made of pine, low-grade maple (and formerly often of ramin, which is now endangered), or other low-quality wood, with inferior plastic ferrules. A quality cue can be expensive and may be made of exotic woods and other expensive materials which are artfully inlaid in decorative patterns. Many modern cues are also made, like golf clubs, with high-tech materials such as woven graphite. Recently, carbon fiber woven composites have been developed and utilized by top professional players and amateurs. Advantages include less flexibility and no worry of nicks, scratches, or damages to the cue. Skilled players may use more than one cue during a game, including a separate cue with a hard phenolic resin tip for the opening break shot, and another, shorter cue with a special tip for jump shots.

Mechanical bridge

[edit]

The mechanical bridge, sometimes called a “rake”, “crutch”, “bridge stick” or simply “bridge”, and in the UK a “rest”, is used to extend a player’s reach on a shot where the cue ball is too far away for normal hand bridging. It consists of a stick with a grooved metal or plastic head which the cue slides on.

Some players, especially current or former snooker players, use a screw-on cue butt extension instead of or in addition to the mechanical bridge.

Bridge head design is varied, and not all designs (especially those with cue shaft-enclosing rings, or wheels on the bottom of the head), are broadly tournament-approved.

In Italy, a longer, thicker cue is typically available for this kind of tricky shot.

For snooker, bridges are normally available in three forms, their use depending on how the player is hampered; the standard rest is a simple cross, the ‘spider’ has a raised arch around 12 cm with three grooves to rest the cue in and for the most awkward of shots, the ‘giraffe’ (or ‘swan’ in England) which has a raised arch much like the ‘spider’ but with a slender arm reaching out around 15 cm with the groove.

Chalk

[edit]

Chalk is applied to the tip of the cue stick, ideally before every shot, to increase the tip’s friction coefficient so that when it impacts the cue ball on a non-center hit, no miscue (unintentional slippage between the cue tip and the struck ball) occurs. Chalk is an important element to make good shots in pool or snooker. Cue tip chalk is not actually the substance typically referred to as “chalk” (generally calcium carbonate), but any of several proprietary compounds, with a silicate base. It was around the time of the Industrial Revolution that newer compounds formed that provided better grip for the ball. This is when the English began to experiment with side spin or applying curl to the ball. This was shortly introduced to the American players and is how the term “putting English on the ball” came to be. “Chalk” may also refer to a cone of fine, white hand chalk; like talc (talcum powder) it can be used to reduce friction between the cue and bridge hand during shooting, for a smoother stroke. Some brands of hand chalk are made of compressed talc. (Tip chalk is not used for this purpose because it is abrasive, hand-staining and difficult to apply.) Many players prefer a slick pool glove over hand chalk or talc because of the messiness of these powders; buildup of particles on the cloth will affect ball behavior and necessitate more-frequent cloth cleaning.

Cue tip chalk (invented in its modern form by straight rail billiard pro William A. Spinks and chemist William Hoskins in 1897)[14][15] is made by crushing silica and the abrasive substance corundum or aloxite[15] (aluminium oxide),[16][17] into a powder.[15] It is combined with dye (originally and most commonly green or blue-green, like traditional billiard cloth, but available today, like the cloth, in many colours) and a binder (glue).[15] Each manufacturer’s brand has different qualities, which can significantly affect play. High humidity can also impair the effectiveness of chalk. Harder, drier compounds are generally considered superior by most players.

Major games

[edit]

There are two main varieties of billiard games: carom and pocket.

The main carom billiards games are straight rail, balkline and three cushion billiards. All are played on a pocketless table with three balls; two cue balls and one object ball. In all, players shoot a cue ball so that it makes contact with the opponent’s cue ball as well as the object ball. Others of multinational interest are four-ball and five-pins.

The most globally popular of the large variety of pocket games are pool and snooker. A third, English billiards, has some features of carom billiards. English billiards used to be one of the two most-competitive cue sports along with the carom game balkline, at the turn of the 20th century and is still enjoyed today in Commonwealth countries. Another pocket game, Russian pyramid and its variants like kaisa are popular in the former Eastern bloc.

Games played on a carom billiards table

[edit]

Main article: Carom billiards

Straight rail

[edit]

Main article: straight rail

In straight rail, a player scores a point and may continue shooting each time his cue ball makes contact with both other balls. Some of the best players of straight billiards developed the skill to gather the balls in a corner or along the same rail for the purpose of playing a series of nurse shots to score a seemingly limitless number of points.

The first straight rail professional tournament was held in 1879 where Jacob Schaefer Sr. scored 690 points in a single turn[13][page needed] (that is, 690 separate strokes without a miss). With the balls repetitively hit and barely moving in endless “nursing”, there was little for the fans to watch.

Balkline

[edit]

Main article: Balkline

In light of these skill developments in straight rail, the game of balkline soon developed to make it impossible for a player to keep the balls gathered in one part of the table for long, greatly limiting the effectiveness of nurse shots. A balkline is a line parallel to one end of a billiards table. In the game of balkline, the players have to drive at least one object ball past a balkline parallel to each rail after a specified number of points have been scored.

Cushion billiards

[edit]

Main articles: one-cushion caroms and three-cushion billiards

Another solution was to require a player’s cue ball to make contact with the rail cushions in the process of contacting the other balls. This in turn saw the three-cushion version emerge, where the cue ball must make three separate cushion contacts during a shot. This is difficult enough that even the best players can only manage to average one to two points per turn. This is sometimes described as “hardest to learn” and “require most skill” of all billiards.

Games played on a pool table

[edit]

Main article: Pool (cue sports)

There are many variations of games played on a standard pool table. Popular pool games include eight-ball, nine-ball, straight pool and one-pocket. Even within games types (e.g. eight-ball), there may be variations, and people may play recreationally using relaxed or local rules. A few of the more popular examples of pool games are given below.

In eight-ball and nine-ball, the object is to sink object balls until one can legally pocket the winning eponymous “money ball“. Well-known but waning in popularity is straight pool, in which players seek to continue sinking balls, rack after rack if they can, to reach a pre-determined winning score (typically 150). Related to nine-ball, another well-known game is rotation, where the lowest-numbered object ball on the table must be struck first, although any object ball may be pocketed (i.e., combination shot). Each pocketed ball is worth its number, and the player with the highest score at the end of the rack is the winner. Since there are only 120 points available (1 + 2 + 3 ⋯ + 15 = 120), scoring 61 points leaves no opportunity for the opponent to catch up. In both one-pocket and bank pool, the players must sink a set number of balls; respectively, all in a particular pocket, or all by bank shots. In snooker, players score points by alternately potting red balls and various special “colour balls“.

Two-player or -team games

[edit]

- Eight-ball: The goal is to pocket (pot) all of one’s designated group of balls (either stripes vs. solids, or reds vs. yellows, depending upon the equipment), and then pocket the 8 ball in a called pocket.

- Nine-ball: The goal is to pocket the 9 ball; the initial contact of the cue ball each turn must be with the lowest-numbered object ball remaining on the table; there are numerous variants such as seven-ball, six-ball, and the older forms of three-ball and ten-ball, that simply use a different number of balls and have a different money ball.

- Straight pool (a.k.a. 14.1 continuous pool): The goal is to reach a predetermined number of points (e.g. 100); a point is earned by pocketing any called ball into a designated pocket; game play is by racks of 15 balls, and the last object ball of a rack is not pocketed, but left on the table with the opponent re-racking the remaining 14 before game play continues.

- Bank pool: The goal is to reach a predetermined number of points; a point is earned by pocketing any called ball by banking it into a designated pocket using one or more cushion.

Speed pool

[edit]

Speed pool is a standard billiards game where the balls must be pocketed in as little time as possible. Rules vary greatly from tournament to tournament. The International Speed Pool Challenge has been held annually since 2006.

Games played on a snooker table

[edit]

English billiards

[edit]

Main article: English billiards

Dating to approximately 1800, English billiards, called simply billiards[18] in many former British colonies and in the UK where it originated, was originally called the winning and losing carambole game, folding in the names of three predecessor games, the winning game, the losing game and the carambole game (an early form of straight rail), that combined to form it.[19] The game features both cannons (caroms) and the pocketing of balls as objects of play. English billiards requires two cue balls and a red object ball. The object of the game is to score either a fixed number of points, or score the most points within a set time frame, determined at the start of the game.

Points are awarded for:

- Two-ball cannons: striking both the object ball and the other (opponent’s) cue ball on the same shot (2 points).

- Winning hazards: potting the red ball (3 points); potting the other cue ball (2 points).

- Losing hazards (or “in-offs”): potting one’s cue ball by cannoning off another ball (3 points if the red ball was hit first; 2 points if the other cue ball was hit first, or if the red and other cue ball were “split“, i.e., hit simultaneously).

Snooker

[edit]

Main article: Snooker

Snooker is a pocket billiards game originated by British officers stationed in India during the 19th century, based on earlier pool games such as black pool and life pool. The name of the game became generalized to also describe one of its prime strategies: to “snooker” the opposing player by causing that player to foul or leave an opening to be exploited.

In the United Kingdom, snooker is by far the most popular cue sport at the competitive level, and major national pastime along with association football and cricket. It is played in many Commonwealth countries as well, and in areas of Asia, becoming increasingly popular in China in particular. Snooker is uncommon in North America, where pool games such as eight-ball and nine-ball dominate, and Latin America and Continental Europe, where carom games dominate. The first World Snooker Championship was held in 1927, and it has been held annually since then with few exceptions. The World Professional Billiards and Snooker Association (WPBSA) was established in 1968 to regulate the professional game, while the International Billiards and Snooker Federation (IBSF) regulates the amateur games.

List of cue sports and games

[edit]

Carom games

[edit]

Main article: Carom billiards

- Artistic billiards

- Balkline

- Four-ball billiards (yotsudama, sagu)

- One-cushion billiards

- Straight rail

- Three-cushion billiards

Pocket games

[edit]

Pool games

[edit]

Main category: Pool (cue sports)

- American rotation

- Artistic pool

- Bank pool

- Baseball pocket billiards

- Bowlliards

- Chicago

- Cribbage

- Cutthroat

- Eight-ball

- Blackball (a.k.a. eightball pool, British-style eight-ball)

- Chinese eight-ball

- Equal offense

- Fifteen-ball

- Honolulu

- Kelly pool

- Killer

- Nine-ball

- One-pocket

- Rotation (a.k.a. 61)

- Seven-ball

- Speed pool

- Straight pool (a.k.a. 14.1 continuous)

- Ten-ball

- Three-ball

Non-pool pocket games

[edit]

Snooker games

[edit]

Games with pockets and caroms

[edit]

Obstacle and target games

[edit]

- Bagatelle

- Bar billiards

- Bumper pool

- Danish pin billiards

- Five-pin billiards

- Goriziana (or nine-pin billiards)

Disk games

[edit]

- Novuss (uses full-length cues)

Cueless games

[edit]

Main category: Finger billiards

Main games

[edit]

| Game | Carom | Pool | Snooker | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Image | |||||

| Table | Length | Total | 3.065-3.115 meters | 107.875–115.125 inches (2.7400–2.9242 m) (9 feet)98.875–107.125 inches (2.5114–2.7210 m) (8 feet) | |

| Playing surface | 2.79-2.89 meters | 100–100.125 inches (2.5400–2.5432 m) (9 feet)92–92.125 inches (2.3368–2.3400 m) (8 feet) | 140–141 inches (3.6–3.6 m) | ||

| Width | Total | 1.6245-1.695 meters | 57.875–65.125 inches (1.4700–1.6542 m) (9 feet)53.875–61.125 inches (1.3684–1.5526 m) (8 feet) | ||

| Playing surface | 1.37-1.47 meters | 50–50.125 inches (1.2700–1.2732 m) (9 feet)46–46.125 inches (1.1684–1.1716 m) (8 feet) | 69.5–70.5 inches (1.77–1.79 m) | ||

| Height | Total | 0.787-0.837 meters | 33.5–34.5 inches (0.85–0.88 m) | ||

| Playing surface | 0.75-0.80 meters | 29.25–31 inches (0.743–0.787 m) | |||

| Pockets | Number | None | 6 | 6 | |

| Corner pockets | 4.5–4.625 inches (11.43–11.75 cm) | ||||

| Side pockets | 5–5.125 inches (12.70–13.02 cm) | ||||

| Ball | Number | 3 | 1 (cue ball)15 (object balls) | 1 (white)15 (red)7 (colored) | |

| Diameter | 6.1–6.15centimeters | 2.25–2.3 inches (5.7–5.8 cm) | 5.2–5.3 centimeters | ||

| Weight | 205-220 grams | 5.5–6 ounces (160–170 g) | |||

| Material | cast phenolic resin plastic | ||||

| Cue | Length | 40 inches (100 cm) | 3 feet (91 cm) | ||

| Tip | 1.4 centimeters (diameter) | ||||

| Weight | 25 ounces (710 g) | ||||

| Tournaments | World nation championship | Yes | |||

| Olympic | No | ||||

| Professional leagues | Yes | ||||